Website

Pages

EXPORT_HUGO_SECTION: ./

EXPORT_HUGO_CUSTOM_FRONT_MATTER: :author false :toc false

Welcome!

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: home

I am an Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. My work focuses on two (often intersecting) areas of philosophy – the History of Modern Philosophy (especially Kant) and the Philosophy of Mind. Here you’ll find links to my research and teaching, as well as the occasional blog post.

If you’re interested, here’s my complete CV: PDF | HTML.

Research

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: research

EXPORT_HUGO_WEIGHT: -100

EXPORT_HUGO_MENU: :menu main

I have broad interests in the philosophy of mind and the foundations of cognitive science, as well as the history of European Modern philosophy from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. My published work to date mostly focuses on the philosophy of Immanuel Kant. I have written on Kant’s views concerning the mind, perception, his theory of human reason and rationality, and the broader metaphysical and epistemological views with which these ideas are integrated. I’m also very interested in seeing what, if any, connections may be made between Kant’s positions and contemporary research programs in the philosophy of mind and metaphysics. In particular, I am interested in issues pertaining to the study of mental content, the nature and significance of self-consciousness, reasoning and rationality, and animal cognition.

Books

-

Kant's Order of Reason: On Rational Agency and Control. Oxford University Press. forthcoming.The aim of Kant's Order of Reason is to give an account of Kant's conception of rational agency that clarifies and explains both the scope and nature of such activity, and elucidates the centrality of Kant's account of rational determination for his mature critical philosophy. As I see it, the core Kantian insight concerning rational determination is that the capacity for rationality is based in and derived from the capacity for exercising a very specific kind of causality in the world–namely, f…Read more

Published articles

-

Rationality: What difference does it make? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 1-26. forthcoming.A variety of interpreters have argued that Kant construes the animality of human beings as ‘transformed’, in some sense, through the possession of rationality. I argue that this interpretation admits of multiple readings and that it is either wrong, or doesn’t result in the conclusion for which its proponents argue. I also explain the sense in which rationality nevertheless significantly differentiates human beings from other animals.

-

“I Am the Original of All Objects”: Apperception and the Substantial Subject. Philosophers' Imprint 20 (26): 1-38. 2020.Kant’s conception of the centrality of intellectual self-consciousness, or “pure apperception”, for scientific knowledge of nature is well known, if still obscure. Here I argue that, for Kant, at least one central role for such self-consciousness lies in the acquisition of the content of concepts central to metaphysical theorizing. I focus on one important concept, that of <substance>. I argue that, for Kant, the representational content of the concept <substance> depends not just on the capacity…Read more

-

Kantian Conceptualism/Nonconceptualism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2020.Overview of the (non)conceptualism debate in Kant studies

-

On the Transcendental Freedom of the Intellect. Ergo: An Open Access Journal of Philosophy 7 35-104. 2020.Kant holds that the applicability of the moral ‘ought’ depends on a kind of agent-causal freedom that is incompatible with the deterministic structure of phenomenal nature. I argue that Kant understands this determinism to threaten not just morality but the very possibility of our status as rational beings. Rational beings exemplify “cognitive control” in all of their actions, including not just rational willing and the formation of doxastic attitudes, but also more basic cognitive acts such as …Read more

-

Animals and Objectivity. In Lucy Allais & John Callanan (eds.), Kant and Animals, Oxford University Press. pp. 42-65. 2020.Starting from the assumption that Kant allows for the possible existence of conscious sensory states in non-rational animals, I examine the textual and philosophical grounds for his acceptance of the possibility that such states are also 'objective'. I elucidate different senses of what might be meant in crediting a cognitive state as objective. I then put forward and defend an interpretation according to which the cognitive states of animals, though extremely limited on Kan…Read more

-

Motion and the Affection Argument. Synthese 195 (11): 4979-4995. 2018.In the Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science, Kant presents an argument for the centrality of <motion> to our concept <matter>. This argument has long been considered either irredeemably obscure or otherwise defective. In this paper I provide an interpretation which defends the argument’s validity and clarifies the sense in which it aims to show that <motion> is fundamental to our conception of matter.

-

Intuition and Presence. In Andrew Stephenson & Anil Gomes (eds.), Kant and the Mind, Oxford University Press. pp. 86-103. 2017.In this paper I explicate the notion of “presence” [Gegenwart] as it pertains to intuition. Specifically, I examine two central problems for the position that an empirical intuition is an immediate relation to an existing particular in one’s environment. The first stems from Kant’s description of the faculty of imagination, while the second stems from Kant’s discussion of hallucination. I shall suggest that Kant’s writings indicate at least one possible means of reconciling our two problems with…Read more

-

Getting Acquainted with Kant. In Dennis Schulting (ed.), Kantian Nonconceptualism, Palgrave-macmillan. pp. 171-97. 2016.My question here concerns whether Kant claims that experience has nonconceptual content, or whether, on his view, experience is essentially conceptual. However there is a sense in which this debate concerning the content of intuition is ill-conceived. Part of this has to do with the terms in which the debate is set, and part to do with confusion over the connection between Kant’s own views and contemporary concerns in epistemology and the philosophy of mind. However, I think much of the substanc…Read more

-

Kant on Perceptual Content. Mind 125 (497): 95-144. 2016.Call the idea that states of perceptual awareness have intentional content, and in virtue of that aim at or represent ways the world might be, the ‘Content View.’ I argue that though Kant is widely interpreted as endorsing the Content View there are significant problems for any such interpretation. I further argue that given the problems associated with attributing the Content View to Kant, interpreters should instead consider him as endorsing a form of acquaintance theory. Though perceptual acq…Read more

-

Kant: Philosophy of Mind. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2015.Kant: Philosophy of Mind Immanuel Kant was one of the most important philosophers of the Enlightenment Period in Western European history. This encyclopedia article focuses on Kant’s views in the philosophy of mind, which undergird much of his epistemology and metaphysics. In particular, it focuses on metaphysical and epistemological doctrines forming the … Continue reading Kant: Philosophy of Mind →.

-

Two Kinds of Unity in the Critique of Pure Reason. Journal of the History of Philosophy 53 (1): 79-110. 2015.I argue that Kant’s distinction between the cognitive roles of sensibility and understanding raises a question concerning the conditions necessary for objective representation. I distinguish two opposing interpretive positions—viz. Intellectualism and Sensibilism. According to Intellectualism all objective representation depends, at least in part, on the unifying synthetic activity of the mind. In contrast, Sensibilism argues that at least some forms of objective representation, specifically int…Read more

-

The Kantian (Non)‐conceptualism Debate. Philosophy Compass 9 (11): 769-790. 2014.One of the central debates in contemporary Kant scholarship concerns whether Kant endorses a “conceptualist” account of the nature of sensory experience. Understanding the debate is crucial for getting a full grasp of Kant's theory of mind, cognition, perception, and epistemology. This paper situates the debate in the context of Kant's broader theory of cognition and surveys some of the major arguments for conceptualist and non-conceptualist interpretations of his critical philosophy

-

Kant on Animal Consciousness. Philosophers' Imprint 11. 2011.Kant is often considered to have argued that perceptual awareness of objects in one's environment depends on the subject's possession of conceptual capacities. This conceptualist interpretation raises an immediate problem concerning the nature of perceptual awareness in non-rational, non-concept using animals. In this paper I argue that Kant’s claims concerning animal representation and consciousness do not foreclose the possibility of attributing to animals the capacity for objective perceptual…Read more

-

Three Skeptics and the Critique: Review of Michael Forster's Kant and Skepticism. Philosophical Books 51 (4): 228-244. 2010.A long critical notice of Michael Forster's recent book, "Kant and Skepticism." We argue that Forster's characterization of Kant's response to skepticism is both textually dubious and philosophically flawed. -/- .

Book reviews

-

Fellow Creatures, by Christine Korsgaard. Oxford University Press, 2018. ISBN 0198753853. 272 pp. $24.95. European Journal of Philosophy 28 (1): 258-262. 2020.

-

Kant and the Demands of Reflection. SGIR Review 2 (1): 42-59. 2019.From an author meets critics session on Melissa Merritt's *Kant on Reflection and Virtue*.

-

The Mind's "I". European Journal of Philosophy 27 (1): 255-265. 2019.Critical notice of Béatrice Longuenesse's book *I, Me, Mine*.

-

Waxman on Intuition and Apperception. Critique. 2018.A critical discussion of Waxman's recent book, Kant's Anatomy of the Intelligent Mind

-

Kant's Transcendental Deduction: An Analytical‐Historical Commentary, by Henry Allison. Oxford University Press, 2015, 496 pp. ISBN 13: 978‐0‐19‐872485‐8 hb £75.00. European Journal of Philosophy 25 (2): 546-554. 2017.

-

: From Empiricism to Expressivism: Brandom Reads Sellars. Ethics 126 (3): 808-816. 2016.One of the better known of the many bons mots of the Sellarsian corpus concerns his definition of philosophy: it is the attempt to understand “how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term.” When applied to Sellars’s philosophy in particular, one might be forgiven for doubting the possible success of such an endeavor. Richard Rorty once quipped of Sellars’s followers that they were either “left-wing” or “right-wing,” emphasizing on…Read more

-

Comments on Lucy Allais, Manifest Reality. Critique. 2016.Extended critical discussion of Lucy Allais, *Manifest Reality*

-

Comments on Stefanie Grüne's *Blinde Anschauung*. Critique. 2014.Extended critical discussion of Stefanie Grüne's *Blinde Anschauung*

Work in Progress

If you’re interested in a draft of any of the following please email me.

- “Kant on Reflection”

- “On the Freedom of the Intellect”

Upcoming Conferences & Presentations

- November 2018. “On the Freedom of the Intellect.” University of Nebraska–Omaha. Omaha, NE.

- February 2019. Author Meets Critics Session on Melissa Merritt, Kant on Reflection and Virtue. Meeting of the Central Division of the APA. Denver, CO.

Teaching

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: teaching

EXPORT_HUGO_WEIGHT: -50

EXPORT_HUGO_MENU: :menu main

I regularly teach the The Philosophy of Food (PHIL 105), Introduction to Philosophy (PHIL 101), an undergraduate survey of ’modern’ philosophy of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (PHIL 232), and undergraduate and graduate level courses on Kant and related topics (PHIL 460/860, PHIL 471/871, and PHIL 971).

Previously Taught

- PHIL 232 (Yearly): History of Early Modern Philosophy

- PHIL 101 (Yearly): Introduction to Philosophy

- PHIL 105 (Yearly): The Philosophy of Food

- PHIL 971 (Fall 2017): Self-Knowledge in Kant & Early German Idealism

- PHIL 971 (Spring 2016): Introspection & Self-Knowledge

- PHIL 971 (Fall 2013): Seminar on Conceptualism

- PHIL 460/860 (Fall 2016): Kant & Early Modern Philosophy

- Oxford Grad Seminar (Trinity 2017) on Kant on perception and cognition, with Anil Gomes

Resources

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: resources

EXPORT_HUGO_WEIGHT: 0

EXPORT_HUGO_MENU: :menu main

Here I collect links for research, teaching, technology, and whatever else might be useful.

Philosophy Links

Reading & Writing Philosophy

- Philosophical Terms & Methods

- Jim Pryor’s guides to reading and writing philosophy

- Critical Thinking

- Purdue Online Writing Lab

- A Guide to Philosophical Writing

- Writing a Thesis Statement

- Philosophy Paper Structure

Kant Related Links

- KantPapers

- Kant in the Classroom

- Kant on the Web

- Kant-Forschungsstelle

- Early Modern Philosophy Texts

- Kant Akademieausgabe (Courtesy of Universität Bonn)

- Database of Kant’s concepts for a theory of nature

Sources for online German texts

Academic Technology & Tools

Links to tools I use for research and writing

- Markdown: Plaintext markup for easy writing

- Pandoc: File conversion

- Emacs: A superb (and free) text editor and writing/research platform

- If you want to get started with emacs you might take a look at my configuration file

- BibDesk: Reference manager for bib files (Free, OS X only)

- Skim: PDF reader & annotator (Free, OS X only)

- Zotero: A great free way to collect and manage references. Works well with bibtex via zotero better bibtex

- Git: Version control

- Github: Online storage and collaboration

- Kieran Healy’s writing resources page

- Profhacker: Blog on teaching & technology

- The Programming Historian: Tutorials for aspiring digital humanists

Contact

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: contact

EXPORT_HUGO_MENU: :menu main

EXPORT_HUGO_WEIGHT: 10

Dr. Colin McLear

Office: 1003 Oldfather Hall

Office Hours: T 1:00-3:20 and by appointment

Email: mclear@unl.edu

Email is the best way to reach me. I answer emails as soon as I can, but primarily only on weekdays.

Blog

EXPORT_HUGO_SECTION: posts

EXPORT_HUGO_CUSTOM_FRONT_MATTER: :toc false :type post

DONE Moving to Hugo

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: moving-to-hugo

Another summer, another excuse to tinker with my website. I’ve used pelican, a python static site generator, to run this website for nearly six years. It’s a great tool. But I dislike python dependency hell, and pelican is a bit slow. So I’ve looked elsewhere. Hugo is blazing fast, has a thriving community, decent templates, and a downloadable binary that you can get via homebrew. No more dependency management! Also important for me (as an emacs user), there is a great org-mode exporter—ox-hugo—that lets me easily generate the web content from an org-file. On the whole I’ve been very happy with the move.

I’ve also changed hosting from github to Netlify, which provides dead-simple hosting. All you do is point it at a git repository (which remains on Github) and tell it what commands to run and it provides continuous deployment. So whenever I make a change to the site and push that change to my repository on Github Netlify automatically regenerates the site. Very cool. Plus, easy https for a more secure site.

DONE Maintaining a CV in Multiple Formats

EXPORT_DATE: 2015-12-14

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: maintaining-cv-multiple-formats

EXPORT_HUGO_CUSTOM_FRONT_MATTER: :aliases /2015/maintaining-a-cv-in-multiple-formats :type post :toc false

Suppose you want to keep a CV accessible in PDF, html, and perhaps other formats (e.g. docx). It’s a pain to do them all individually and keep them in sync. Here’s one way to avoid that issue, though it has a bit of initial work involved in setting everything up. What you want to do is keep your CV (or really anything of that ilk that you want to have available in multiple formats) in a YAML file and then use pandoc to convert the YAML file into whatever documents you need. I got the idea from looking at this template on Github.

What you want to do is keep the CV info in a YAML file like so:

name: Immanuel Kant

address: Königsberg, Prussia

email: manny@copernicanrevolution.edu

AOS:

- Aesthetics, Epistemology, Ethics, Metaphysics, Philosophy of Mind, Political Philosophy

AOC:

- German Idealism, Philosophy of Religion

experience:

- years: 1770-1804

employer: University of Königsberg

job: Chair of Logic and Metaphysics

city: Königsberg, DEUsing pandoc, you can then convert this into a variety of formats, including HTML and PDF. The key is to create a template for every output format that you need. For example, you might template your employment history like so:

$for(experience)$

$experience.years$\\

\textsc{$experience.employer$}\\

\emph{$experience.job$}\\

$experience.city$\\[.2cm]

$endfor$Pandoc then feeds the YAML info to LaTeX for PDF typesetting. You can see a sample here.

With this method, you can keep your entire CV in a single YAML file and

easily generate a PDF, HTML, or some other format. For the full set of

templates for LaTeX and HTML, along with a makefile for easy

conversion, you can look at

my repo on Github.

DONE New Site Design

EXPORT_DATE: 2015-07-13

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: newsite

I’ve updated the website with (what I hope is) a cleaner look and a bit better navigation. Thanks go to DandyDev for developing a great bootstrap theme for Pelican. I’ll be continuing to tweak here and there so apologies if you find broken links or other infelicities.

DONE Pandoc Letters

EXPORT_DATE: 2015-07-22

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: pandocletter

I had to write a recommendation letter today and thought I’d use it as an excuse to write up a Pandoc template for Pandoc-LaTeX conversion. It generates a nice looking letter with letterhead (assuming you have a logo for it). It uses the newlfm package. The template is on github here. I got the idea from Matthew Miller’s post, and this discussion on texblog.org.

DONE Site Changes

EXPORT_DATE: 2016-05-28

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: sitechanges

I’m making some changes to the website over the next couple weeks. I’m moving all the teaching materials to their own websites (e.g. phil105.colinmclear.net). So please excuse any broken links you find in the meantime!

DONE Text Editors and Academic Writing

EXPORT_DATE: 2016-09-05

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: texteditor

EXPORT_HUGO_CUSTOM_FRONT_MATTER: :aliases /2016/text-editors-and-academic-writing :type post :toc false

Tools for writing using a computer fall into two broad camps. On the one side we have WYSIWIG word processing applications like Microsoft Word, Apple Pages, and Google Docs. They allow not only the typing of text but also real-time formatting and display. These applications are familiar to most, and are the dominant ones used in higher-ed today. They also tend to be expensive (or available only to those with institutional affiliation), suffer from issues of feature-bloat and unnecessary make-overs, and use proprietary non-human-readable file formats.

In contrast to the WYSIWIG editors stands the text editor. It operates on plain text, human readable, files. And its main purpose is to parse text in the most efficient way possible. It does not (typically) display a page as it will look when printed. There are many, many text editors one can choose from them, and the two most well-known—emacs and vim—are free.

As far as I can tell there are basically three main reasons to prefer a text editor over a word processing application.

- Text editors are more efficient at editing text

- Text editors connect better with other research and writing tools

- Text editors are easier to enjoy working in/with

I’m not sure that I find any of these or the many other various arguments for writing in plain text with a text editor totally convincing, at least in isolation. Certainly there is no one-size-fits-all answer. If you like writing in MS Word or Apple Pages, if such programs help you get on with writing, then great.

That said, there are some really useful things that you can do when writing in plain text and using a powerful (and often free) text editor, or command line tools made for manipulating text (like cat, grep or sed). Here are a few reasons that I find compelling. I’m sure there are others.

Search

Whether searching in a single file or across files, when writing in plain text it is really quite simple to perform searches looking for a particular word or combination of words. If you know the syntax for writing regular expressions the process is even easier. For example, from a directory of notes I can search for the occurrence of particular words or phrases and then move to each occurrence (even if they are in separate files) seamlessly, all using just a text editor (emacs) and a simple search command (in this case using emacs to interface with a search program called the silver searcher or “ag”).

Version control

I’ve written before about how useful it is to have your writing under some sort of version control. Most modern text editors allow you to directly and easily interface with the vc of your choice in the course of an editing session. In the case of emacs there is the incomparable Magit.

Outlining & Notetaking

Since their main use is manipulating text, text editors are unsurprisingly great for outlining and notetakeing. For example, Vim has a great outlining tool called Voom and emacs has the incomparable org-mode. You can even use org-mode for keeping a research wiki if that’s you’re thing. You can see a historian making use of vim’s notetaking powers here.

Flexibility

Do you spend a lot of time on your computer at night and wish MS Word wasn’t such a blaringly bright white application to work with? Do you wish you could automate or create keyboard shortcuts for repetitive tasks during editing? At least with the three major open source editors—emacs, vim, and atom—this is relatively easy to do (or to learn to do). You can change how your editor looks, what kind of keyboard combinations do what, and automate simple (or even complex) tasks.

Interface with other programs

Though this connects with the second bullet point above, it is useful to emphasize. For example, I use pandoc for converting all my academic writing and teaching materials. I also keep all my bibliographic material in a bibtex document. My text editor has plug-ins which allow me to seamlessly interact with these programs and others, without having to leave the editor. I’m also able to do all the upkeep for my various websites within the editor. I’ve found this kind of uniform interface for everything to be extremely useful.

So try a text editor (or two or three) and see what you think (but really, use emacs). Write your next paper in it (or at least the notes for it) and see if you find it helpful. There is always a learning curve to take into account. But after you get the hang of a particular editor you can decide whether it is really a help or if you’d rather just chuck it and go back to MS Word, Pages, or whatever worked for you before.

DONE Version Control and Academic Writing

EXPORT_DATE: 2015-07-17

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: versioncontrol

EXPORT_HUGO_CUSTOM_FRONT_MATTER: :aliases /2015/version-control-and-academic-writing :type post :toc false

Academic writing typically requires writing something in drafts. Many drafts. Until recently there have been few ways of elegantly handling this. Often, one would need to title the current draft with the day’s date, then save this draft in a folder (named, e.g., “drafts” or “versions”), and do this every time one sits down to write. This works, in some ways. The data is there. The problem is that you quickly end up with a folder (or desktop’s) worth of files. These filenames have typically ridiculous and increasingly obscure titles (e.g. final-draft-final-revision\final-draft-04-2018.docx). And it is seldom clear, using this method, exactly what one did when, without actually opening a particular file and looking, or trying to remember when (and where) it was that one made the relevant change.

Nowadays, especially if you use some sort of cloud-based word-processor, it’s likely that you have access to various ways of looking at your version history. For example, Google docs has a revision history option (something similar exists for Dropbox, which lets you easily move back and forth among different versions. Revision histories of this kind offer a way to automatically back up one’s writing. This is especially helpful if you’re not the type of person to carefully name each day’s writing with a new time/date stamp and save them all in the appropriate folder. There are also service (as opposed to application) specific ways of tracking changes to a file. At least some of them allow you to compare differences between versions of files. But at least two things are missing. First, there is no straightforward way of seeing what has changed where, and to see this at arbitrary levels of granularity. Second, in order to see what’s changed when, you have to look in the document itself. There is no general log of the changes you’ve made to the file.

Here’s what I have in mind:

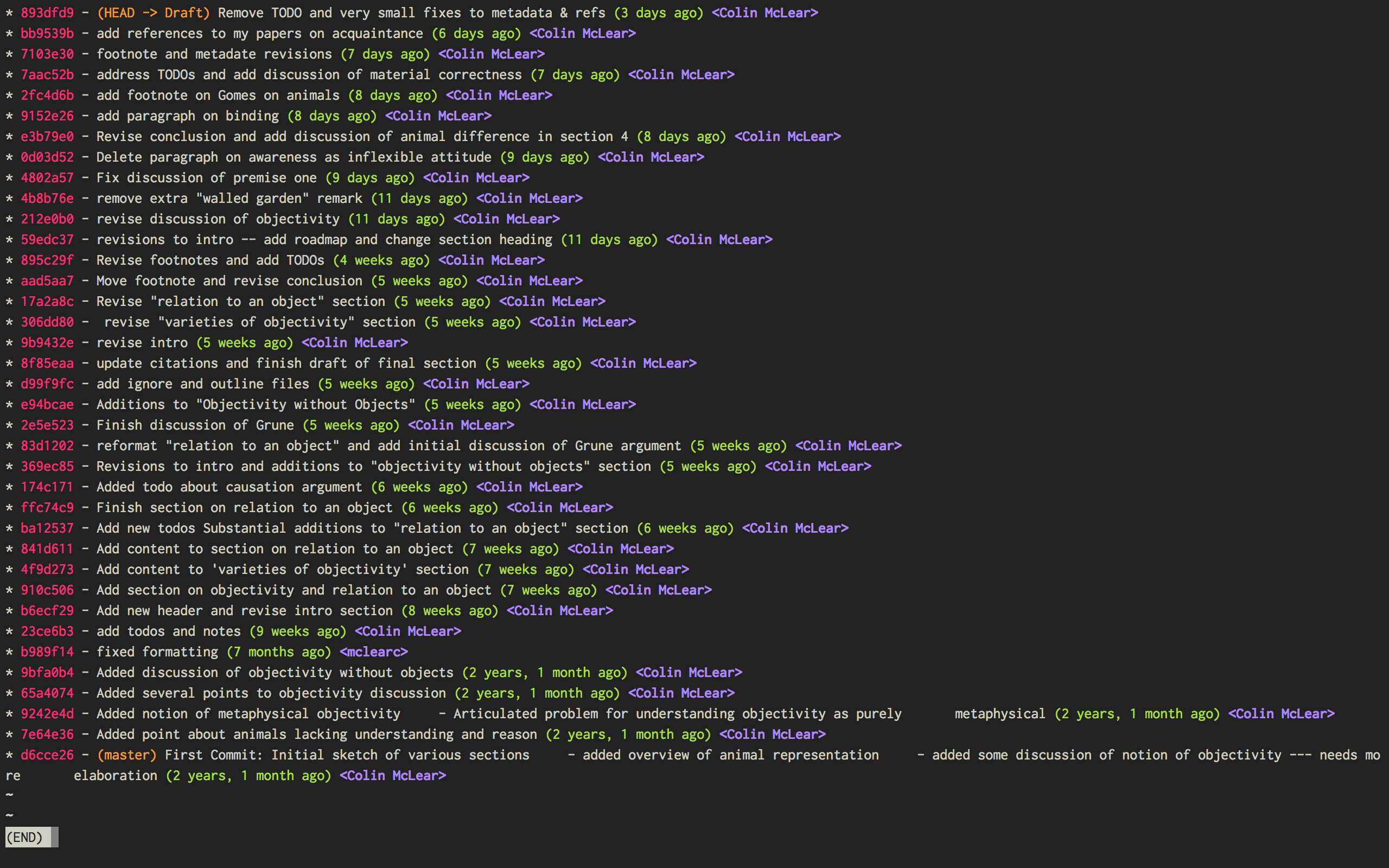

Figure 1: Change Log

You see here a series of entries going back over two years, with a description of what I took to be the most important changes at the time. I can then open any one of the those entries and see a more detailed, line by line, description of changes. This is called a “diff”. I can also roll back the version of the file I’m working on to any of these changes. Each “commit” is a snapshot of the relevant files at the time, which I can retrieve at any point.

I think this is a really nice way to track and visualize one’s progress on some piece of writing. This is hard to do with standard word processors and their means of versioning, but very straightforward to do with a more sophisticated kind of version control system. A version control system can manage changes to a file at an extremely fine level of grain–down to a line or character if necessary. While this system was originally adopted by programmers, it can also be very useful in academic writing (or really any writing where multiple drafts are created).

This form of version control pictured above depends on a system called Git.

The basic idea is that, using whatever writing application one likes, one tracks changes to a document, or a whole directory of documents (e.g. adding image files for presentations, or additional parts of a document kept in separate files when writing longer works like a thesis or novel). The changes can be tracked at an arbitrary level of grain–to the sentence, word, or character–and different versions can be easily compared. All of this can be done without generating lots of files with different numbers or date/time stamps. Everything is kept in a database that one can easily interact with using either the command line or some form of graphical interface.

So far, this isn’t necessarily any different from what one can do using Word or Google Docs. One additional benefit of using a version control system is that one can easily label and describe batches of changes (e.g. revisions to a particular section of a paper or chapter) and keep a single record of these changes. Then, if one want to look back at one’s progress, or for a specific change that one made, all one need do is look at the single general document listing the changes. You can even do this in the text editor of your choice (e.g. vim or sublime text)

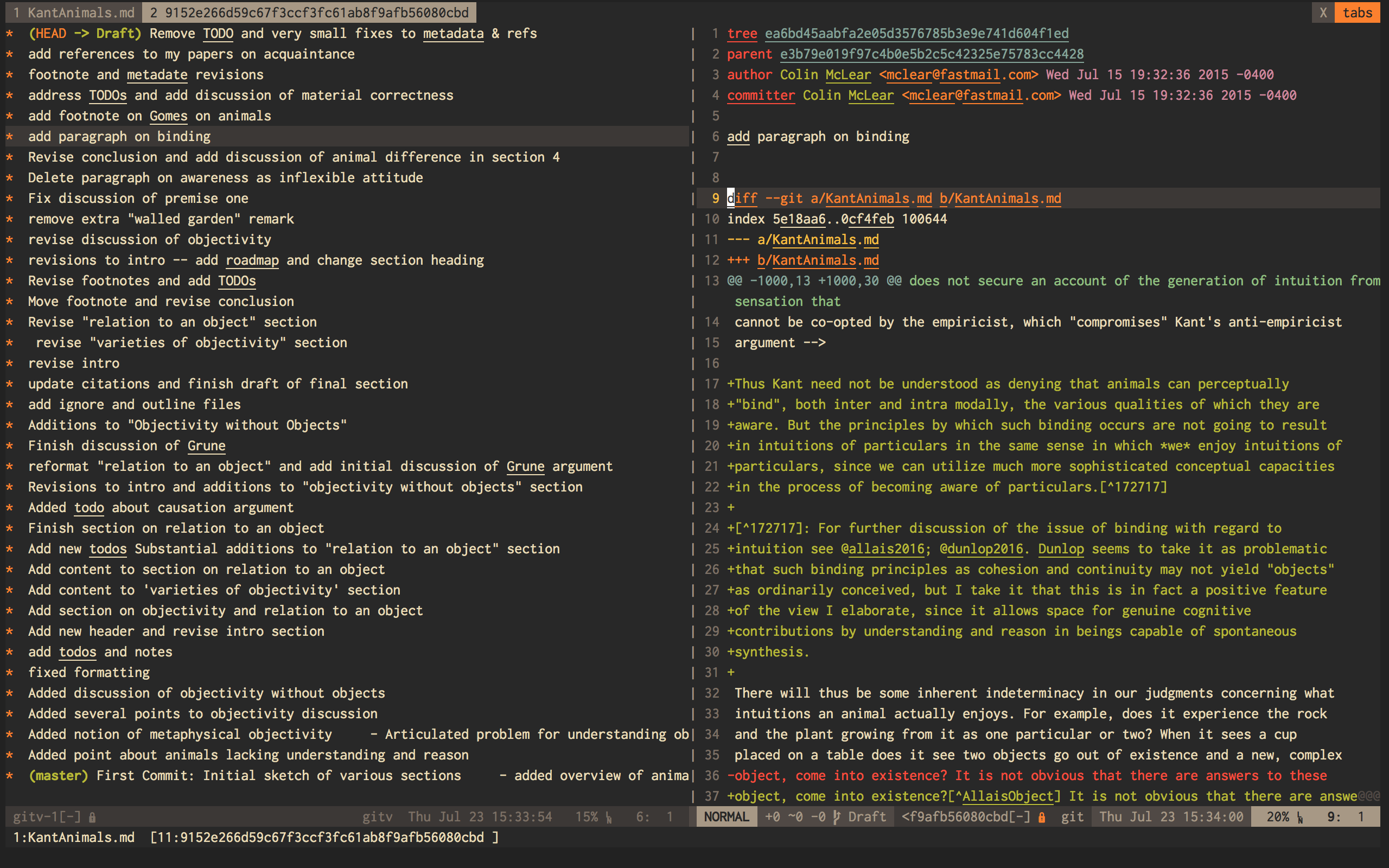

For example, here’s a sample log of the changes made to a paper I’ve been working on, using a vim plugin called “gitv”, which depends on Tim Pope’s fugitive plugin (SublimeGit is an equally excellent sublime text plugin).

On the left is the git log of changes. On the right is a more detailed description of what changed–what was added, deleted, or moved.

Using Git

The basic workflow for using Git is as follows. In the directory you’re

keeping your project in (you do keep this in a directory and not just on

your desktop right?) you need to create a Git repository. This means

typing git init on the command line from the directory, or doing so

via whatever GUI app you’ve picked. You only have to do this once per

writing project. So that’s:

cd \path\to\repositorygit initgit add filename.filegit commit- write commit message

- write and quit file

Once you’ve got your repository (or “repo”) you need to add files for

tracking. Just type git add and the name of the file you’re tracking.

Then type git commit. You’ll then type a commit message to go along

with the commit–e.g. “first commit”. Write and quit, or press commit in

whatever application you’re using. At this point you’ve got a

functioning version control system. So your workflow should be something

like the following:

- Write

- Add/stage changes

- Write commit message and commit

There’s a lot to Git that I can’t cover here. It can be very helpful when experimenting with an idea. It’s also a nice way to think about and track your work over time. One downside of using a system like git is that it doesn’t work well with Microsoft Word or other rich text WYSIWIG text editors. But there are ways around this.

If you like the idea of git, commit messages, and a readable log of changes you’ve made to a file, but don’t want to deal with the more technical aspects of setting up git and using it, there are also great web apps like Penflip, which streamline much of the process.

DONE Writing a syllabus for multiple formats

EXPORT_DATE: 2016-07-17

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: syllabus_yaml

I find it generally preferable to keep information I use for teaching in a format that allows for different styles of presentation. I’ve written before about how one might keep a CV in a yaml document that outputs to a variety of different possible formats using pandoc. I also use a similar system for syllabi.

The basic idea is to keep your syllabus in a yaml file and export it to html, pdf, or rtf using a makefile. The nice thing about this is that you can, e.g., hand out a nicely formatted PDF (or printout) of your syllabus at the beginning of the semester, and then keep a continually updated version on your course website as HTML, all without having to have multiple documents that you’re editing. You can find the basic template on Github and an example from my PHIL 101 class, also on Github.

The html and latex templates are pretty basic, but serviceable. You should be able to easily modify them to fit your particular needs.

DRAFT On Citations

EXPORT_DATE: 2016-10-11

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: citations

DRAFT Reference Management

EXPORT_DATE: 2015-08-05

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: reference-management

There are two things I wish I had better habits for in grad school—note taking, and managing references. I’ll touch on them both here, but I’m mainly going to focus on managing references.

I read a lot, and I skim even more. I want a tool that will help me do three things. First, I want to be able to keep track of what I’m reading, preferably across multiple devices (e.g. an ipad and a laptop). This is easy if you read one thing at a time, and never start reading anything else until you’ve finished the previous item. But I don’t work that way—perhaps the Internet has caused my short attention span. I’m usually reading several things at once, and often circle back around to one thing after I’ve started something else.

Second, I want to be able to keep track of notes concerning what I’m reading. This is easily done in the margins (if you’re not working electronically, as I almost always am) or in a notebook. But these are data silos. I want something that I can easily get data out of later.

Third, I want to be able to easily cite what I’ve read in my writing. So, I want three things—reading, annotation, and citation management.

DRAFT Taking Notes

EXPORT_FILE_NAME: taking-notes

DRAFT Reading Efficiently

See http://karinwulf.com/efficient-reading/